The Strangers Case

Anyone who has not experienced the genius of Shakespeare knows not what they are missing. Here, in a speech from the unfinished play Sir Thomas More, Shakespeare again demonstrates his brilliance.

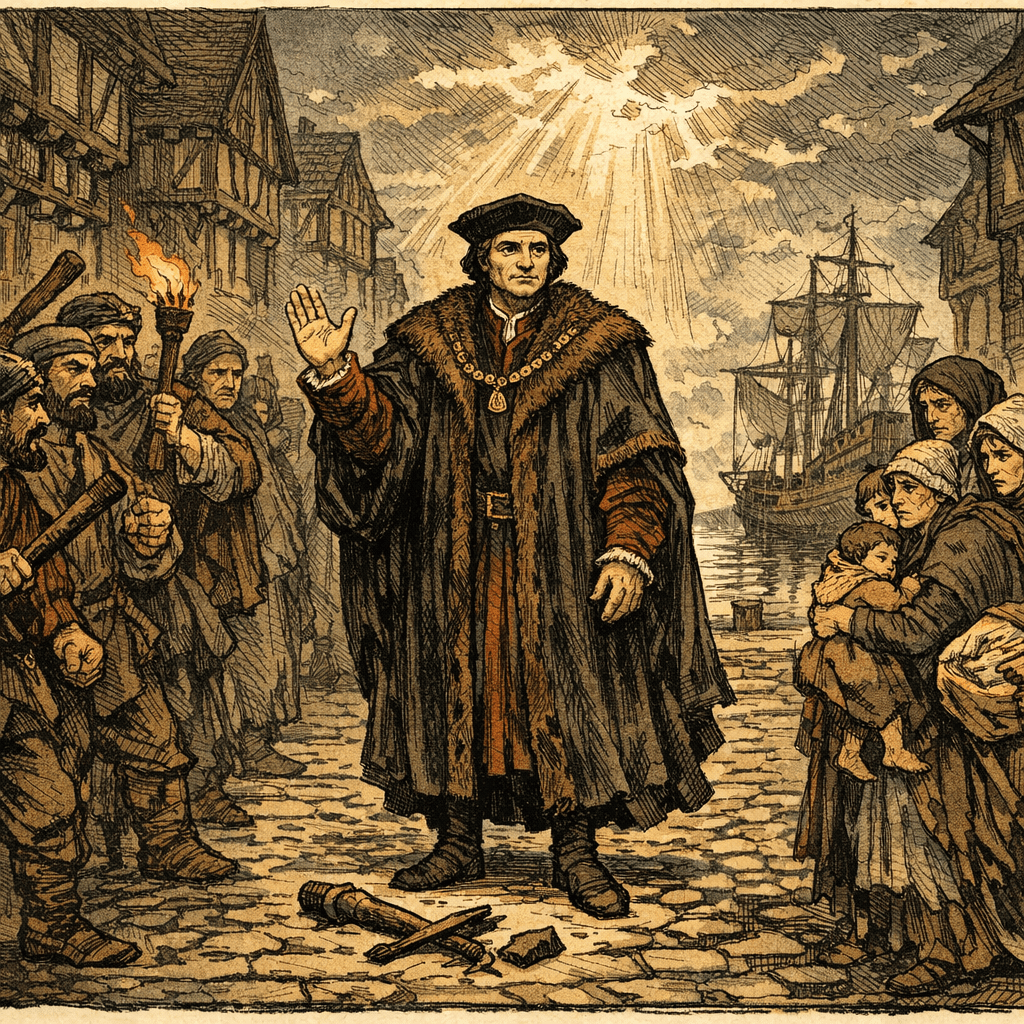

On May 1, 1517 — now referred to as Evil May Day — riots broke out in London as a response to an influx of immigrant workers. This play, written some eighty years later and attributed to Shakespeare, was never performed, likely due to censorship, yet could not be more appropriate for the age in which we find ourselves.

My point is to underscore the fact that the overwhelming majority of those who’ve entered the country unlawfully are human beings that have done nothing more than seek a better life for themselves and their families. Yes they’ve committed a crime but, given the same challenges they face in their native countries—desperation, violence, starvation, torture, death—who wouldn’t break a minor law if it saved your life or the lives of those you love?

We are using them as pawns in the game of politics and overlooking their humanity in the pursuit of justice that bears little resemblance to the ideals of American exceptionalism.

We are better than this. We can find a way to protect our borders, enforce our laws, and preserve our humanity. They are not mutually exclusive. But we need to remind ourselves what is the most important part of that. And if you don’t believe it is preserving our humanity, we are in grave trouble.

And if you want to experience the full power of this speech, search Ian McClellan’s off the cuff performance on Stephen Colbert’s show.

However you experience it you have to be touched by its powerful message.

Grant them removed, and grant that this your noise

Hath chid down all the majesty of England;

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage,

Plodding to the ports and coasts for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires,

Authority quite silent by your brawl,

And you in ruff of your opinions clothed;

What had you got? I’ll tell you: you had taught

How insolence and strong hand should prevail,

How order should be quelled; and by this pattern

Not one of you should live an agèd man,

For other ruffians, as their fancies wrought,

With self same hand, self reasons, and self right,

Would shark on you, and men like ravenous fishes

Would feed on one another.

[…]

Say now the king,

As he is clement if th’offender mourn,

Should so much come too short of your great trespass

As but to banish you, whither would you go?

What country, by the nature of your error,

Should give you harbor? Go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, to Spain or Portugal,

Nay, anywhere that not adheres to England,

Why, you must needs be strangers: would you be pleased

To find a nation of such barbarous temper,

That, breaking out in hideous violence,

Would not afford you an abode on earth,

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owed not nor made not you, nor that the elements

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But chartered unto them, what would you think

To be thus used? This is the strangers’ case;

And this your mountainish inhumanity.