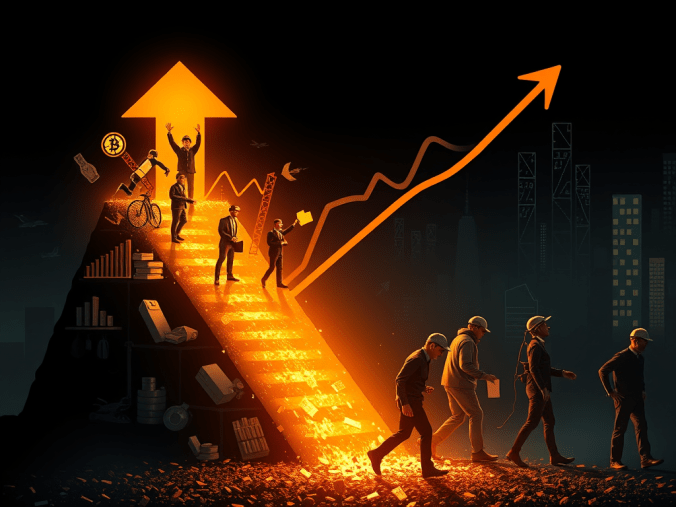

The US is in a K-shaped economy. It is characterized by extreme growth in the high-end sector at the expense and detriment of the lower and medium wage sector. While many sing the praises of this administration’s economic policy (if one could even describe what that policy is) the reality for most Americans is not a positive economic outlook.

A K‑shaped economy describes a recovery or growth pattern where different parts of the population experience sharply different outcomes simultaneously. One group’s economic prospects rise (the upward arm of the “K”), while another group’s prospects fall or stagnate (the downward arm). This term became common during and after the COVID‑19 pandemic to explain uneven economic recovery.

Effects on lower‑income Americans

Lower‑income Americans are typically on the downward side of the “K” and face several challenges:

- Job insecurity: Many lower‑wage jobs are concentrated in service, retail, hospitality, and gig work, which are more vulnerable to layoffs, reduced hours, and automation.

- Slower wage growth: Even when employment recovers, wages for low‑income workers often lag behind inflation, reducing real purchasing power.

- Limited asset ownership: Lower‑income households are less likely to own stocks, real estate, or other assets that usually grow during economic recoveries, so they miss out on wealth gains.

- Rising cost pressures: Increases in housing, food, healthcare, and transportation costs hit lower‑income families harder because these expenses make up a larger share of their income.

- Reduced economic mobility: Gaps in savings, education access, and job training can make it harder to move into higher‑paying roles as the economy changes.

Bottom line: In a K‑shaped economy, overall growth can mask widening inequality, with lower‑income Americans experiencing prolonged financial hardship.

What the K‑Shaped Economy Means for Workers

Workers on the downward side of the K face intersecting challenges that unions confront daily:

- Unequal recovery: Office‑based and managerial jobs rebounded quickly, while service, manufacturing, logistics, healthcare support, and food service jobs remain volatile despite being essential to the economy.

- Falling real wages: Even where nominal wages went up, inflation—especially in housing, food, and healthcare—has eaten away at paychecks, leaving many workers worse off.

- Precarious employment: More workers are employed part‑time, on temporary contracts, or misclassified as independent contractors, limiting access to benefits and job security.

- Unsafe and demanding conditions: Productivity demands have gone up without corresponding improvements in safety, staffing, or compensation.

- Weakened worker voice: Decades of declining union density and weak labor law enforcement have reduced workers’ ability to bargain collectively for fair wages and conditions.

A K‑shaped economy is a direct consequence of declining worker power. When workers cannot collectively negotiate, economic gains flow upward instead of being shared. Union jobs consistently deliver higher wages, safer workplaces, better benefits, and greater economic stability—making unions a key solution to K‑shaped inequality.

Since the Trump administration often blames Biden for everything, here is the reality of the many causes of the high rate of inflation resulting from Global, not exclusively domestic, conditions. Biden faced unprecedented global economic pressures requiring innovative and challenging responses. Yet his policies managed to slow and then reduce inflation from it peak of 9% to a generally accepted 3% level.

Here is a single‑row table summarizing the primary cause of inflation under Biden, as described by mainstream economic research (Fed, NBER, FactCheck): These conclusions are easily verifiable.

| Inflation under Biden (2021–2022) | Primary cause |

| Rapid inflation surge to ~9% | Post‑COVID demand rebounded faster than supply, while supply chains were still constrained; fiscal stimulus boosted demand, and energy/food shocks from the Ukraine war pushed prices to their peak |

In one sentence: Inflation was mainly caused by too much demand chasing too little supply after COVID, with stimulus and global energy shocks making it worse.

Primary cause (the core driver)

Demand rebounded faster than supply after COVID

- As the economy reopened in 2021, consumer spending surged while production, labor supply, and logistics were still constrained.

- Pandemic supply‑chain disruptions (ports, chips, autos, shipping) limited how fast goods and services could be produced, pushing prices higher when demand jumped.

[factually.co], [nber.org]

This demand‑supply mismatch is widely identified as the central mechanism behind the inflation takeoff.

Major amplifiers (what made it worse)

1. Large fiscal stimulus

- Pandemic‑era stimulus (including the $1.9T American Rescue Plan) added significant purchasing power while the economy’s supply capacity was still impaired.

- Research and fact‑checks conclude stimulus contributed meaningfully, though estimates vary on how much.

[nber.org], [politifact.com]

Most mainstream analyses say stimulus was a contributor, not the sole cause. And, with inflation now closer to the standard model, the termination of the program will eliminate necessary and long-term benefits from the program targeting infrastructure improvements, environmental progress, and adapting to a changing energy focus from fossil fuels to renewables.

2. Global energy and food shocks

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 caused sharp increases in oil, gas, and food prices, pushing inflation to its peak.

- Energy prices spill into transportation, manufacturing, and groceries, affecting nearly everything.

[factually.co], [nber.org]

3. Tight labor markets

- Job openings far exceeded available workers in 2021–2022.

- Rising wages added cost pressure in services, contributing to “sticky” inflation later on.

[nber.org]

What it was not

- Inflation was not unique to the U.S.; it surged across advanced economies after COVID.

- That global pattern supports the conclusion that pandemic and energy shocks mattered greatly, not just U.S. policy.

[chicagofed.org]

One‑sentence summary

Inflation under Biden was primarily caused by a rapid post‑COVID demand rebound colliding with constrained supply, then intensified by fiscal stimulus and global energy shocks—especially the Ukraine war.

Then there’s this, from a posting by Ken Block on social media.

“Have the tariffs negatively impacted the US economy?

Yup.

A $12 billion “Farmer Bridge Assistance” program, also known as a bailout, will provide up to $155,000 to each “row crop” farm (soybean farms are the most affected).

The bailout mitigates financial losses from trade disputes and the impact of reciprocating tariffs.

Farmers are calling this aid a “drop in the bucket” and a short-term band-aid rather than a solution to their economic crisis. Farmers estimate this aid covers only about 25% of the economic harm they have endured since Trump lit up his tariff war.

Worse, China has stopped buying US soybeans altogether and has replaced our soybean exports with soybeans from other countries. There is a real risk that our soybean farmers have lost the Chinese market for good. Other countries have also replaced US exports with goods from non-US sources. Economic isolation, as well as isolation stemming from the US’s unfriendly posture toward many of the countries we trade with, means a loss of crucial markets that we may never fully regain.” Ken Block, Author of Disproven (https://kenblock.com/DISPROVEN.html)

And do yourself a favor and read Ken Block’s book, Disproven. In light of recent statements by President Trump and his administration continuing the spread of the lie that the 2020 election was stolen and rife with fraud, the threat to the free and open elections outside the control of government is an existential one.