You are twenty-years old, thousands of miles from your home in Pawtucket, RI, it is nine days after D-Day 1944. You are flying your first mission as a Flight Engineer/Top Turret gunner on a B-17 Flying Fortress Tail Number 43-37727.

Your target is a railroad marshalling yard in Angouleme, France supplying troops and ammunition to German forces.

It is the 149th mission flown by the 351st Bombardment Group 508th Squadron since they entered the war. All you have to do is fly twenty-five missions and they will send you home.

Your chances of survival are 25 to 33% of achieving this goal.

You are flying at 25000 feet over the target. Enemy fighters and flak surround the box formation of thirty-nine B-17s.

It takes seven hours of flying time from Polebrook England to the target and back. On this mission, no aircraft are lost but several are damaged, and some airmen wounded by anti-aircraft fire and flak.

But you have survived.

Two days later, another mission over France, The next day, a mission over Hamburg, Germany. Between 15-Jun-1944 and 6-Aug-1944 you’ve flown twenty-two missions. Three more missions and you get to go home.

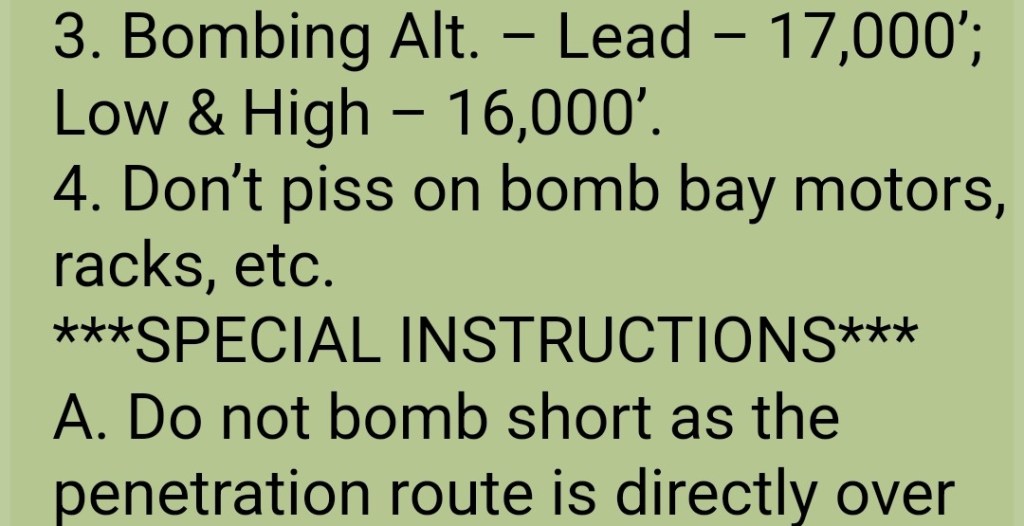

8-Aug-1944 B-17 tail number 43-37900 Mission target St. Sylvain France. Target is Enemy troop concentration 1000 yards in front of Allied Forces. Due to cloud cover only the lead box of bombers hit the target, the rest are directed to secondary sites.

Flak is intense and accurate. You rotate your turret looking for any enemy fighters, ready to fire at any target. The adrenalin surges masking the frigid air in the unheated, unpressurized cabin.

A flak round explodes, shattering the glass and steel of the turret. The shrapnel destroys your right elbow and tears the tissue from your upper arm. In the midst of the bomb run, no one can leave their stations to help you.

It will take two and a half hours to get back to England. The crew will do what they can for you, but you have to survive on just that alone.

For you the war is over. You won’t make the twenty-five missions, but you will survive. You’ll face months of rehabilitation, eventually accepting the fact that your right arm is there but mostly useless.

What do you do about it?

This is the story of my uncle, Edward T. Broadmeadow. Born in Pawtucket RI in 1923, he was of the generation tasked with fighting in WWII. I recall the times we were at his house, or he and his family at ours, and his condition was never the focus of his world.

He was just Uncle Ed, who called us all “agate smashers” and made us laugh at his antics.

He did what he did, not because others expected it of him, but because he expected it of himself. And he accepted the consequences of his actions and went on with his life.

He didn’t have a handicap plate. Never sought any special treatment because of his wounds. He came home, married the love of his life, raised four boys to become outstanding young men, and appreciated the life he got to live unlike so many others who also found themselves in the skies over Germany.

What triggered this piece was watching the show Masters of the Air. One gets a sense of what it must have been like to fly in the “Forts” and face the horrors of war. The boredom in between missions and the sheer terror during them.

In doing some research on this, with the help of my cousin Edward, Uncle Ed’s oldest son, I found a site called 351st.org. It catalogs the missions of the 508th throughout the war.

Going down the rabbit hole online, I found an interesting fact. The first aircraft my uncle flew on, tail number 43-37727, was also one he flew several other missions on. On the mission where he was wounded, his crew flew in a spare aircraft while 37727 was being repaired.

Two days after he was wounded, 43-37737 was shot down with all crew lost over Germany.

The odds were against him, and yet twenty-three times Ed crawled into a B-17, took up his position, and followed his conscience.

They were called the greatest generation, but the reality is it was not the generation, it was the individuals within it whose sense of duty and honor compelled them to act as they did. What differentiates them from other generations is they expected nothing more than a chance to return to their lives.

In the generations since, it seems an expectation they are owed something has overwhelmed any sense of obligation to others. While not universally true—there are many examples of courage in almost every generation—it does seem to be more common.

We have twenty-year-olds who cannot handle the slightest bit of criticism, difference of opinion, or expectation of standards. One has to wonder if that old saying has some truth in it. At the risk of being politically incorrect—another characteristic of our age—I will repeat it.

“Bad times make strong men. Strong men make good times. Good times make weak men. Weak men make bad times.”

One can debate whether or not the generation who fought in WWII was the greatest. What one cannot question is that people like my Uncle Ed were heroes of the highest caliber, both in how they fought and how they came home and lived their lives.

I just wish I had appreciated more when he was among us and asked him about those moments over Germany, there was a priceless opportunity there and I missed out on it.

JEBWizard Publishing (www.jebwizardpublishing.com) is a hybrid publishing company focusing on new and emerging authors. We offer a full range of customized publishing services. Everyone has a story to tell, let us help you share it with the world. We turn publishing dreams into reality.

Great story Joe, enjoyed reading it. You are correct that the generation your Uncle was part of is one we may never see again; they just don’t make em like Uncle Ed anymore!

LikeLike

Thanks, Steve. And they certainly don’t

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this story about your Uncle Ed and his generation, Joe. Thanks.

LikeLike

Thanks Jamie

LikeLike